The maestro behind Star Wars and Jaws calls much film scoring “ephemeral”—what he meant, who’s reacting, and what changes next.

Why this landed like a thunderclap

TubiTV Just Hit 200 Million Users – Here’s Why

10 Perfect-Score Shows Buried on Prime Video Right Now

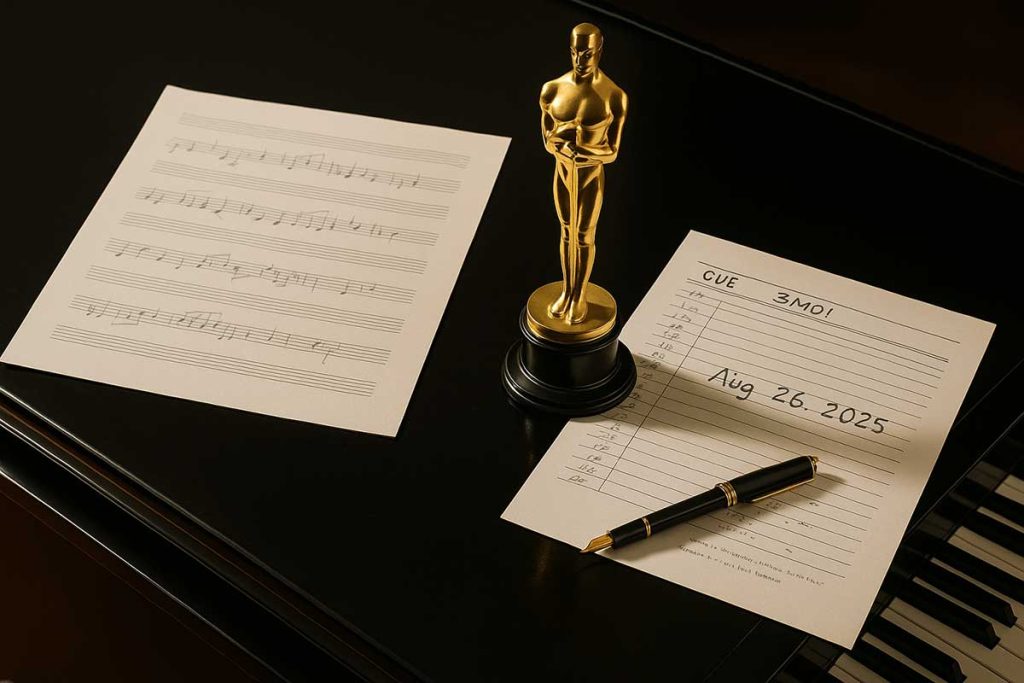

When John Williams—the architect of cinema’s most recognizable themes—says, “I never liked film music very much,” the remark hits with seismic force. Published on August 26, 2025, the 93-year-old composer’s comments reframed how Hollywood talks about its own soundtracks, from their artistic value to their shelf life. Williams contrasted concert works with movie scores, calling most film music “fragmentary” and “ephemeral,” a provocation precisely because it comes from the medium’s most decorated ambassador. The statement doesn’t erase his affection for composing; rather, it challenges the industry’s complacency about what qualifies as lasting musical art. It also arrives in a moment when studios, streamers, and awards bodies are re-evaluating budgets, risk tolerance, and what constitutes “event” craftsmanship. If the standard-bearer says the bar isn’t high enough, expect everyone—from producers and directors to guild voters and music supervisors—to look harder at the music’s narrative purpose, complexity, and staying power.

What he actually said—and how it reverberated

In the interview published this week, Williams argued that even “good” film music usually offers only flashes—an “eight-minute stretch here and there”—and that audiences often love it through nostalgia rather than intrinsic musical heft. He also described film scoring as “just a job,” a modest framing that jarred precisely because his “jobs” became culture’s permanent soundtrack: from Star Wars and Jaws to E.T., Jurassic Park, Schindler’s List, and Indiana Jones. Early reactions from industry watchers zeroed in on two things: first, the uncomfortable mirror he’s holding up to Hollywood’s output; second, the humility that coexists with the critique. Biographer Tim Greiving emphasized that Williams’s stance isn’t false modesty—he’s genuinely skeptical of film music as concert art, even while taking the craft dead seriously. That tension explains why his words travel: he’s not sniping from the outside; he’s interrogating the form he helped define, asking whether it’s still pushing itself beyond familiar motifs and fan-service catharses.

The numbers that make the critique impossible to ignore

The $3.99 Streaming Service With 500+ Oscar Winners Nobody Knows About

Cancel These 3 Subscriptions Before November 1st – Here’s Why

Strip away the discourse and the résumé remains staggering. Williams is the most Oscar-nominated living person with 54 nominations and five wins; he’s also collected dozens of major awards across Grammys, BAFTAs, Emmys, and Golden Globes. He’s written themes that function like global folk songs—melodies instantly legible across generations and languages. Those statistics do more than burnish legacy; they frame the magnitude of this week’s critique. If anyone can separate affection for cinema from a high bar for musical permanence, it’s the composer whose work routinely outlives marketing cycles and format shifts. Measured in cultural effect, Williams’s cues have launched franchises, minted concert tours, and driven billions in downstream value—from box office to theme parks and streaming rewatch spikes. When the genre’s north star argues that the average score lacks concert-hall durability, studios and composers can’t dismiss it as contrarian branding; it becomes a performance note the entire pipeline has to read.

Why fans and composers are split—even if many agree on the diagnosis

For fans, the comments feel like a gut-check: if the greatest says most film music isn’t concert-grade, are we overrating our nostalgia? Working composers, meanwhile, hear a professional challenge: can they push past temp-track sameness, library-driven palettes, and the streaming-era bias toward wall-to-wall underscore? Supporters of Williams’s view argue that blockbuster scoring often privileges texture and pulse over melody and motif, designing music to be felt but not remembered. Skeptics counter that “memorability” isn’t the only metric, and that modern hybrid scores can be emotionally surgical without yielding hummable themes. Williams’s long partnership with Steven Spielberg is another flashpoint—proof, say admirers, that deep director-composer collaboration births durable musical storytelling. And yet, even his admirers concede the marketplace increasingly favors shorter schedules, committee feedback, and safer choices. That’s why this debate doesn’t die in a news cycle; it maps onto anxieties about creativity, time, and taste in the algorithm age.

What changes next: budgets, briefs, and bolder melodies

No, there’s no legal battle here—just a cultural one—but the practical stakes are real. Expect some studios and prestige labels to make room for more concert-usable suites, longer thematic development, and earlier composer onboarding in the edit. Music supervisors and directors who want their films to feel “crafted” will pitch longer timelines and fewer late-stage needle-drops. Awards campaigners may nudge toward scores with clear thematic arcs and standalone listening value. And composers aiming to break out of the noise could lean into leitmotif, counterpoint, and acoustic color as differentiators—tools Williams wielded to make story structure audible. None of this means abandoning textural modernity; it means restoring musical architecture as a top-tier value. If the industry takes the critique as a dare rather than an insult, 2026’s most talked-about scores may sound less interchangeable and more like narratives of their own—music that doesn’t just prop up scenes but rewires how we remember them.

The long view: separating nostalgia from posterity

Williams’s point isn’t that film music can’t achieve permanence; it’s that the medium’s process too often suffocates it. Concert pieces are written to be the event; film scores are written to serve one. Greatness happens when those missions overlap—when a theme both deepens character and survives the frame. The challenge ahead is structural: giving composers time, trust, and thematic latitude; empowering directors to treat music as story, not spackle; and rewarding audiences for listening, not just feeling. As archives grow and IP cycles spin faster, the scores that endure will be the ones that articulate an idea as clearly as a line of dialogue. That’s the bar the most decorated composer alive just set again—by reminding Hollywood that memorable music isn’t an accident of nostalgia but the product of ambition, craft, and risk.

Sources

https://people.com/john-williams-composer-never-liked-film-music-very-much-11797252

https://ew.com/john-william-slams-modern-movie-music-11797588

https://ew.com/jurassic-world-rebirth-switches-composers-alexandre-desplat-exclusive-11719200

Similar posts:

- John Williams 2025 Remark: 3 Reasons Film Scores Face New Scrutiny

- Why John Williams’ Aug 2025 Quote About Film Music Has 54 Nomination Fans Talking

- Grant Williams Wows Hornets Front Office With an Unforgettable Christmas Surprise!

- Thunder Locks In Jaylin Williams for Three More Years, Beating Free Agency Buzz

- Chet Holmgren’s Epic Clapback to Jalen Williams Following Major Contract Reveal!

Jessica Morrison is a seasoned entertainment writer with over a decade of experience covering television, film, and pop culture. After earning a degree in journalism from New York University, she worked as a freelance writer for various entertainment magazines before joining red94.net. Her expertise lies in analyzing television series, from groundbreaking dramas to light-hearted comedies, and she often provides in-depth reviews and industry insights. Outside of writing, Jessica is an avid film buff and enjoys discovering new indie movies at local festivals.