James Harden and Dwight Howard are two great basketball players with skill-sets that could only compliment each other any more if Howard had a reliable 18-foot jumper. But asking for that would be like getting a Lexus for Christmas, then criticizing where the cup-holders are located.

They don’t “need” a reliable 18-foot jumper. It’d be nice, but isn’t necessary thanks to what’s already there. And what’s already there is basketball’s most foundational two-man sequence: the pick-and-roll. How successful are Harden and Howard running it? If you’ve been paying attention to the Houston Rockets this season, you know it’s a bit like watching a live jack hammer ravage an ant hill.

But how are they so successful? And why don’t the Rockets pound opponents into submission with it until either Harden or Howard passes out from exhaustion? Sports are filled with “pick your poison” scenarios, and in the NBA there’s almost nothing deadlier than a pick-and-roll featuring Harden’s handle and Howard’s magnetic pull.

These two are great on their own and even better working together. Through the season’s first 22 games, here’s a closer look at how they’ve been so successful, and why they need to do it more.

The title of this article contains the word “potentially” because the Rockets do not run nearly enough pick-and-roll action with their two best players.

It hasn’t been that big a deal yet, as lineups that contain Harden and Howard are bettering their opponents by 9.0 points per 100 possessions, and scoring at a rate good enough for second best in the league. But that isn’t a worthy explanation as to why a tandem with such potential would limit itself. Instead of running this action, the Rockets continue to feed Howard in the post even though he’s been inconsistent in one-on-one situations. Not to beat a dead horse, but they really need to cut it out—46.2 percent of his offensive possessions end with post-ups. Howard scores on just 34.9 percent of those opportunities, and 24.2 percent of the time he turns it over.

Does that sound like a reliable offensive solution? Howard remains as rudimentary down low as he was in his last days as Orlando’s franchise everything, which brings us to the pick-and-roll. According to mySyngerySports, Howard’s been used as a roll man just 7.9% of the time. How’s he doing on dives to the rim? He’s Godzilla, averaging 1.31 points per possession (second highest in the league), shooting 73.9%, and turning it over a quarter as often compared to when he’s in the post.

Here’s Howard setting a screen on Trail Blazers guard Wesley Matthews, one of the better on-ball defenders Harden’s gone up against this season. As you can see in the picture below, Harden weaves his way towards the free-throw line in an attempt to force Portland’s big, Meyers Leonard, to come out and guard him. (In an article he wrote on Grantland earlier this season, Zach Lowe taught his previously uninformed readers—aka me—that this practice is known around the league as “snaking.” Harden is very, very good at it.)

Despite executing the plan with precision, Matthews decides to stay with Harden, allowing Howard a free run towards the basket. Poor Leonard (No. 11) is momentarily stuck in no man’s land knowing he’s the next line of defense should Harden attack the rim.

Harden tip-toes just far enough towards Leonard to make him completely forget about Howard, then lobs a perfect pass that results in two easy points for Houston. That play came in a half-court set, with plenty of time on the shot clock for Howard to set an initial solid screen, and Harden the patience he needs off the bounce to manipulate Portland’s defense.

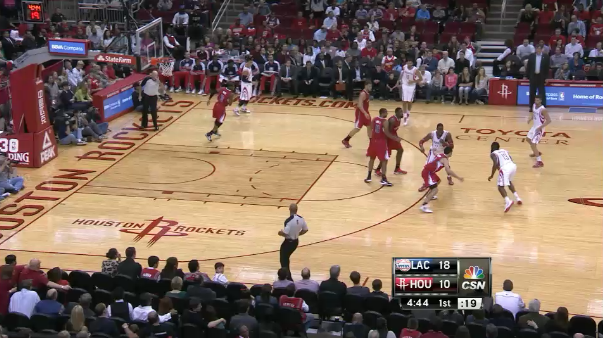

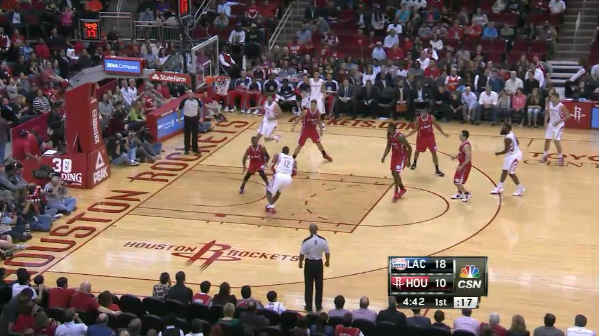

Here we have a Harden/Howard high pick-and-roll that comes in transition, which is something Houston could average well over one point per possession on if they only committed to doing it more often.

First things first, notice where the other three Rockets are located as they run up the court. Jeremy Lin stations himself in the soon-to-be strong side corner, Omri Casspi’s on the wing, and Chandler Parsons trails everything eight feet behind the three-point line. This is all by design, and it’s done to space the court and give the play’s two crucial pieces enough room to operate.

Howard sets a screen on J.J. Redick, and the wheels are in motion.

While Lin, Casspi, and Parsons pull off their duty as compliant onlookers, Howard begins to roll off his screen and is hit on the money with a dauntless pocket pass through DeAndre Jordan’s picket fence fingertips.

Howard receives the pass while moving towards the basket, and the only Clipper standing in his way is little Chris Paul, serving a function he clearly wasn’t built for. (Spoiler Alert: Paul does not block Howard’s dunk.)

Now let’s look at what happens when Harden uses Howard’s screen for his own greedy purposes. We’ll start with the most optimistic scenario I could find.

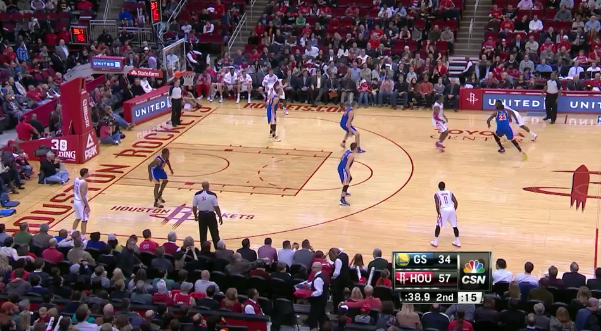

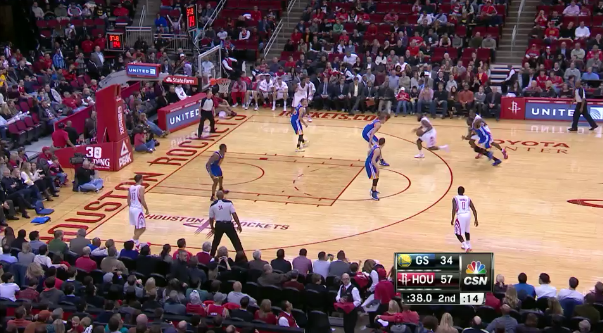

With Warriors forward Draymond Green pressuring Harden 35 feet from the basket (I know Green knows the Rockets are looking to attack in a two-for-one situation, and that his team’s getting blown out in the second quarter, but why would you come out so high? There’s zero chance he can stay with Harden off the dribble) Howard slams him with a flat screen, and from that point on it’s Harden vs. David Lee.

I said this was the most optimistic scenario because it is. James Harden racing towards almost any defender in the NBA would result in at least two shots at the free-throw line. But against Lee, there’s a jamboree taking place in the back of Harden’s head. Needless to say he scores on this possession, albeit on a tricky floater.

When weighed against doing work in the post, high screens from Howard are important for two reasons: 1) His man either comes all the way out of the paint or wades in a treacherous area with the hopeless task of containing Harden, 2) Howard, himself, is clear of any driving/passing/cutting lanes, which can be clogged up when he’s positioned down low.

Harden’s only averaging 5.9 drives per game this season, fewer than Ricky Rubio, Tony Wroten, and Jameer Nelson. If we had access to SportVU’s tracking numbers last year, I’d be willing to bet Harden was far more proficient attacking the rim. But Howard’s here now, and he’s quite large, with a legitimate, deterring presence.

When Howard’s off the floor, 42.6% of Harden’s points are scored in the paint. When the two are together, that number drops to 32.2%. It’s a significant margin, and one that the Rockets don’t like. More screens on the perimeter will get Howard out of the paint, which will create more efficient opportunities for both players.

It’s important to remember that a pick-and-roll’s development is dictated by how the defense chooses to play it. What makes Harden and Howard so lethal is their immediate ability to read what’s happening, then respond with a plan of attack that gives them a high scoring probability. Alley-oop dunks won’t happen every time because other teams will rotate defenders from the weak side. But that’s fine.

Here’s a great example of Harden adapting against one of the league’s smartest and stingiest defenses.

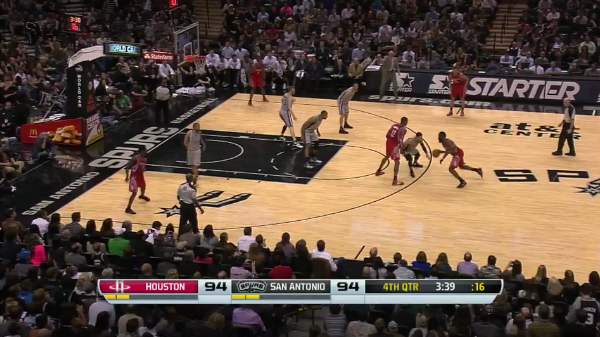

Howard sets a high screen for Harden, with Tim Duncan sagging in the paint, and San Antonio’s other three defenders (not including Danny Green) all in great position to help if needed.

So what does Harden do? He pulls up for a wide open jump shot at the left elbow. It’s a long-two, which is typically frowned upon by Rockets management, but in this case it’s smart and perfect. Driving in on one of the smartest defensive big men who ever lived is an option, sure, but it’d be contested and difficult. Just because Harden doesn’t attempt mid-range jumpers often doesn’t mean he can’t knock them down with ease, as he does here.

This article isn’t a call for Houston to abolish Howard post-ups altogether. But in order for them to maximize his awesome ability there should be more level distribution, with a good portion of his touches allocated to the pick-and-roll.

(Synergy’s numbers are slightly exaggerated; they don’t count plays where Howard sets a screen, rolls to the basket, opens up action elsewhere on the court, and doesn’t receive a pass. But for him to only be finishing less than 10% of his possessions as a roll man is inexcusable.)

We’re not even 25 games into the season, which means Harden and Howard have yet to play 25 professional basketball games together. Their chemistry is solid already and will only get better as the season goes on. Before it’s all said and done, Houston’s coaching staff is too smart not to take advantage of a play that’s essentially their golden ticket.

Michael Pina is a contributor at Red94, CelticsHub, The Classical, Bleacher Report, Sports On Earth, and Boston Magazine. Follow him here.

Leave a Reply